Around two years ago I was browsing online on a typical Saturday evening, and I came across an intriguing post on the Tolkien Collector’s Guide forum, dated September 2019. Someone was asking for a copy of a book entitled: Das erste Jahrzehnt 1977–1987: Ein Almanach, or The First Decade 1977–1987: An Almanac, produced by Klett-Cotta, a German publishing company. In it, so the post claimed, was a copy of a poem written by Tolkien entitled ‘The Complaint of Mim the Dwarf’. And while the replies that followed the original post were helpful in tracking down a copy of the almanac, no other information on the poem itself was forthcoming, except that this version of the poem in the almanac had been translated into German by Hans J. Schütz and titled Mîms Klage.

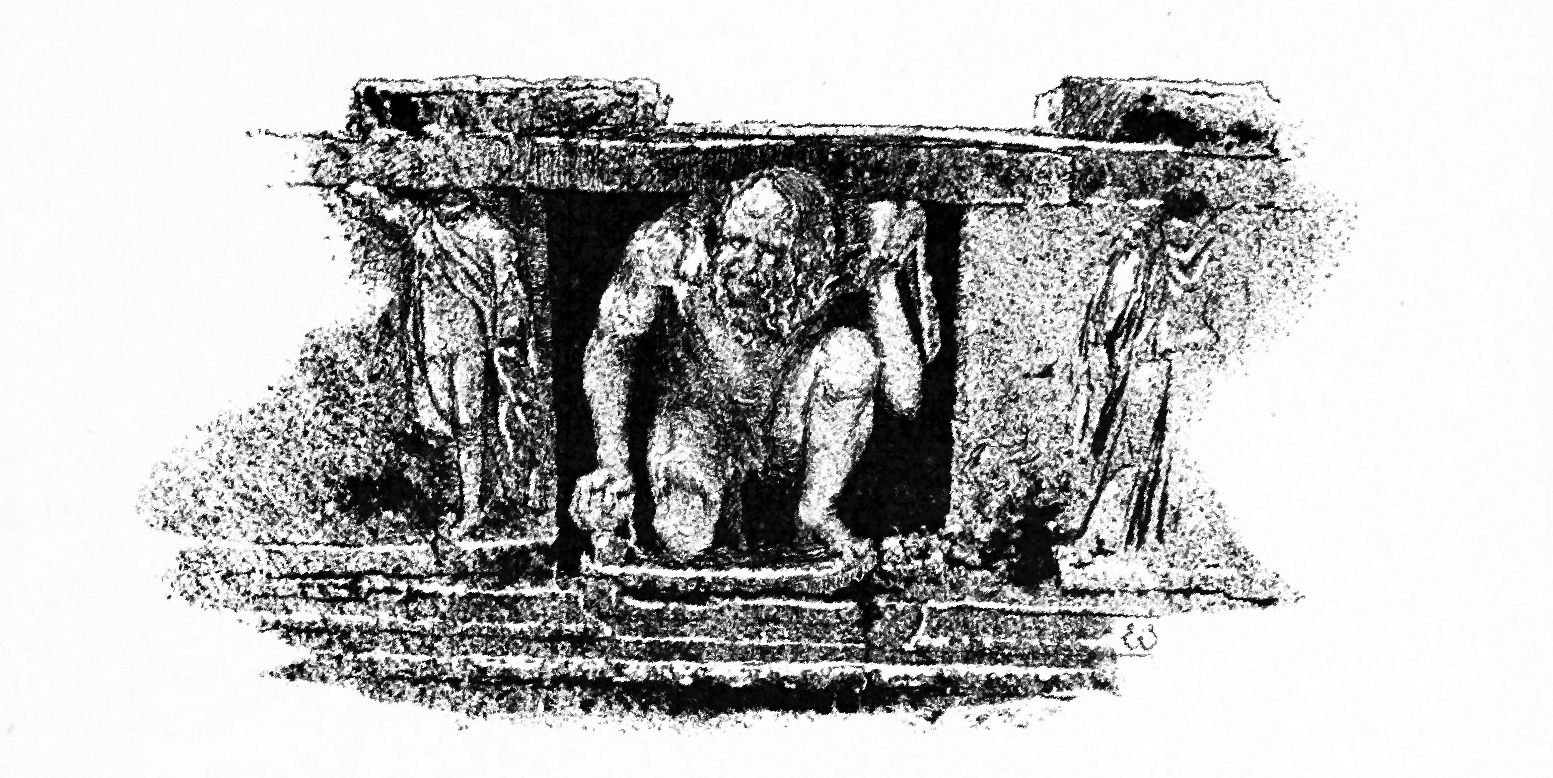

Now, as most of you know Mîm is a character featured in both The Silmarillion and The Children of Húrin. He is what Tolkien calls a petty-dwarf, who were a diminutive race of Dwarves. In the stories, he is involved with Túrin and his band of Outlaws, and later on is ultimately slain by his father Húrin in halls of Nargothrond.

I contemplated long and hard on this, and eventually succumbed to the pressures that come when you cherish a deep passion for anything Tolkien, so I hunted down that particular almanac and acquired a copy for myself. Now, my knowledge of German is extremely limited and I was unable to fully appreciate the words printed on the handful of pages before me. Having said that, I was ecstatic that I had in my collection something not many Tolkien readers had read before (and neither would I it seemed – unless I taught myself German).

And, although the language barrier remained, I discovered much more information on ‘The Complaint of Mîm the Dwarf’; which, in reality, was not just a 26-verse poem, written in decasyllabic rhyming couplets (at least the German translation); but the poem was also accompanied by a three and a half page prose fragment, and was clearly a continuation or an amalgamation to the poem itself. Amid the foreign words, I glimpsed the name Mîm several times, together with the word Zwerg, which I somehow subconsciously remembered it as being the term for Dwarf, and the name Tarn Aeluin – which, as any readers of The Silmarillion will be aware of, is a mountain lake on the Highlands of Dorthonion in the lands of Beleriand; more specifically, the place in which Barahir (father of the famed Beren) and his band of outlaws are forced to flee from after an attack by Orcs.

my knowledge of German is disastrous, and my skills as a language translator were limited to a few amateur exercises I used to attempt for fun years back. So my first port of call was a number of German-English dictionaries and the ever-convenient online translator. I started to transcribe the text from the poem and cross-referencing each word to its corresponding English counterpart, and step-by-step, the first few verses of the poem began to reveal themselves to me. Mîm and the reasons for his lamentations were unlocked, and each line demonstrated Tolkien’s excellent skill of word and language – aware as I was that my English translation was far from ideal; it was a corrupted rendition of a translation from a translation.

Still, I got a glimpse, a tiny glimmer, of the potential beauty of this unpublished work. The poem, now sufficiently legible for me to appreciate each verse and meaning, transformed into this powerful lyric about a wronged Petty-Dwarf whose memory of forging jewels and hardships in exile resonates all the more powerful, especially when one is aware of this character’s past from The Silmarillion and The Children of Húrin. As is the case with much of Tolkien’s poetry, this poem was clearly evocative, atmospheric, powerful and resonant.

So, following that initial exercise of a very basic translation, it was time to refine it even more. A wanted to capture as much as possible Tolkien’s own poetic style, whilst at the same time maintain the use of rhyming couplets for the verses. I confess, this was a really fun stage, as I began experimenting with word changes, playing with tonality and sentence structure, and polishing as much as possible the final aesthetic of the poem.

(C) New Line Cinema

(C) New Line Cinema

The evidence for the existence of both snow-rolls and stone-giants haunting the deep, shadowy passes of Middle-earth is, at best, poor.

The evidence for the existence of both snow-rolls and stone-giants haunting the deep, shadowy passes of Middle-earth is, at best, poor.

© New Line Cinema

© New Line Cinema